2022-04 MIRA Ceti sprak met... Suzanne Ramsay

In de loop van de jaren 1990 was het tijdperk van de reuzentelescopen aangebroken: de twee Keck-telescopen op Hawaï, de Very Large Telescope in het noorden van Chili en de Hobby-Eberly Telescope in het zuiden van de Verenigde Staten zijn er maar enkele van.

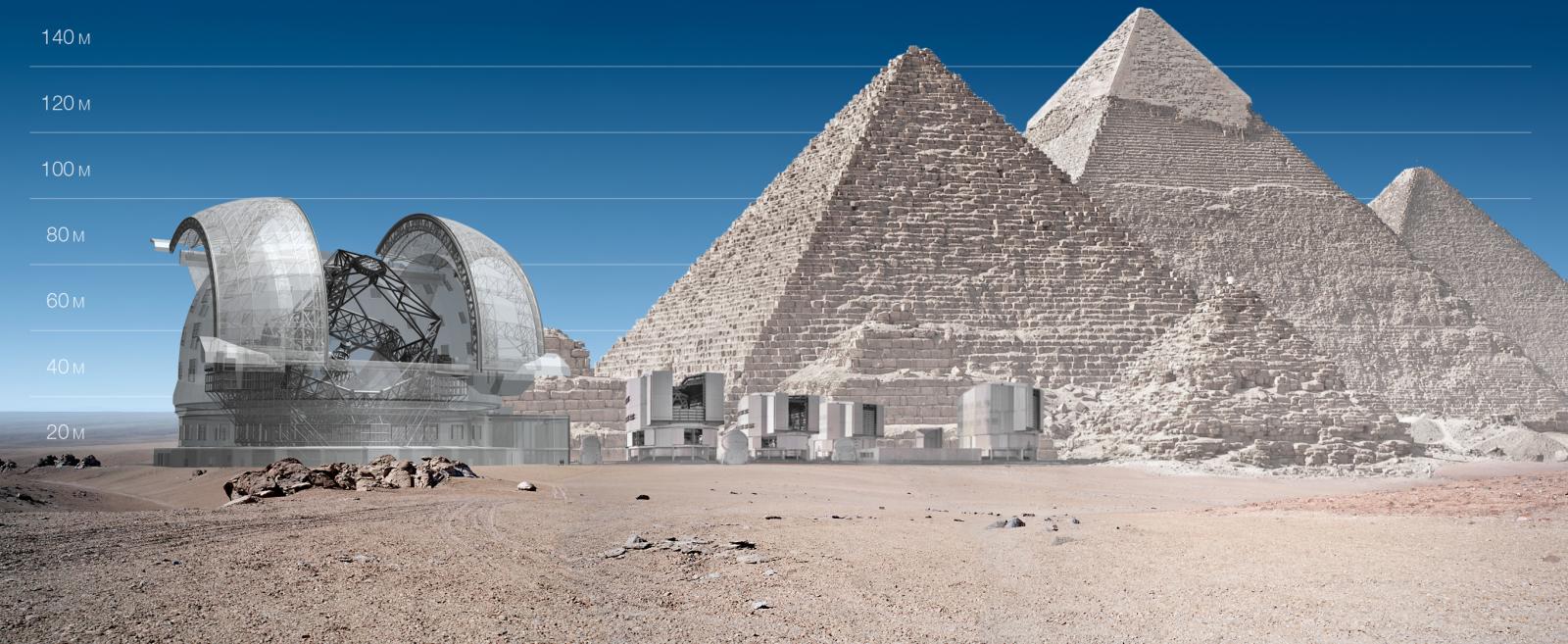

Maar als de Very Large Telescope van de Europese Zuidelijke Sterrenwacht ESO op de berg Paranal in de Atacamawoestijn echt wel Wow is, dan is het project waar de ESO momenteel aan werkt op de Cerro Armazones, niet ver uit de buurt van de VLT, zowaar Wow in het kwadraat.

We spraken over de Extremely Large Telescope die een hoofdspiegel zal hebben met een diameter van 39,3 meter met de Britse sterrenkundige Suzanne Ramsay (°1967), verantwoordelijke voor de wetenschappelijke instrumenten die bij de ELT zullen gebruikt worden.

Opmerking: de Engelse versie van dit interview staat te lezen onder de Nederlandse tekst.

Note: the English version of this interview can be read under the text in Dutch.

Copyright afbeelding: Suzanne Ramsay

Hallo Suzanne, wat fijn om jou te kunnen interviewen via Skype. Hoe ben jij in de wereld van de professionele sterrenkunde terecht gekomen?

Het was pas toen ik aan de universiteit studeerde dat ik besliste om me toe te leggen op sterrenkunde. Ik ben van Glasgow afkomstig en studeerde natuurkunde aan onze universiteit. Je doet dan natuurkunde met best veel wiskunde, en tijdens die studies maakte ik ook grondiger kennis met astronomie. En ik besefte al gauw wat een fascinerende manier sterrenkunde is om de wereld van de natuurkunde echt te doorgronden: je kan het heelal immers zien als een ongemeen interessant en uniek laboratorium.

Het was vervolgens tijdens mijn PhD dat ik geïnteresseerd raakte in de meer praktische kant, namelijk het bouwen van instrumenten voor sterrenkundig onderzoek bij grote telescopen.

Ging jij als jongere ooit naar een sterrenkijkhappening om je te laten overdonderen door de schoonheid van de ringen bij Saturnus of door andere hemelobjecten?

Neen, dat heb ik nooit gedaan. Mijn vader leerde me wel enkele dingen over de sterrenbeelden, en ik herinner me wel ooit als kind een maansverduistering gezien te hebben. Maar in die periode was sterrenkunde zeker niet één van mijn passies, dat kwam bij mij pas heel wat later.

Hoe kwam je van de universiteit in Glasgow terecht bij ESO, de European Southern Observatory?

Na mijn studies in Glasgow trok ik voor mijn PhD niet heel ver weg, naar de universiteit van Edinburgh, hun sterrenkundig instituut bevindt zich in de schoot van de Koninklijke Sterrenwacht op Blackford Hill in Edinburgh.

Daar kon ik meteen beginnen werken aan het instrumentarium voor een project dat al goed opgeschoten was. Delen van het instrument waren in ons laboratorium, bijna klaar om bij de telescoop afgeleverd te worden. Daarnaast kon ik ook sterrenkundig onderzoek doen op het gebied van stervorming. Het project waar het hier over gaat was de infraroodspectrograaf die werd gebouwd voor de UKIRT, de United Kingdom Infra-Red Telescope, op Mauna Kea in Hawaï. Dus voor mijn PhD had ik de buitenkans om naar het beroemde observatorium op Hawaï te gaan waar ook de twee grote Keck-telescopen staan opgesteld. Het was een fantastische ervaring om ons instrument daar te gaan installeren.

Vervolgens had ik het geluk dat ik gedurende lange tijd in Edinburgh kon blijven. Ik was staflid van het Observatorium en dat zowat twintig jaar lang. In die periode werkte ik aan het project van ESO in verband met het installeren van de meest geschikte instrumenten voor de Very Large Telescope in Chili. En ik was ook erg geïnteresseerd om mee te werken aan het ontwikkelen van de instrumenten voor de Extremely Large Telescope, de ELT, die ESO sinds de laten jaren 1990 was beginnen plannen. Dus toen de positie vrij kwam om te gaan werken voor de instrumentatieafdeling van de ESO was dit voor mij een echte buitenkans, en ik was echt heel gelukkig dat ik aangeworven werd en me voortaan voltijds kon gaan bezighouden met het instrumentenproject bij de ELT.

Hoe voelt het om deel uit te maken van de ELT, mogelijk de grootste optische telescoop ooit?

Het is zeker de grootste optische telescoop op het aardoppervlak die momenteel gebouwd wordt. Of er later ooit nog een grotere gebouwd zal worden, dat weten we niet en dat zal de toekomst uitwijzen.

En ja, bij de ELT zijn ook de instrumenten enorm groot en het is een hele uitdaging om daarmee bezig te zijn, dus dat is allemaal erg boeiend. Alles wat we doen gebeurt voor de eerste keer op deze schaal. Het is soms best beangstigend als je erover nadenkt hoe groot de instrumenten zijn, wat er allemaal bij komt kijken om ze te bouwen, daar zijn ongelooflijk veel mensen bij betrokken.

Dus we werken hard opdat wat we doen oké is en dat we uiteindelijk al de wetenschappelijke ontdekkingen zullen kunnen doen waar we zo enorm naar uitkijken. De ELT is een gigantisch project waar teams van overal in Europa aan meewerken, het gaat letterlijk om honderden wetenschappers en ingenieurs. En het is zeker superleuk om daar deel van uit te maken, en van alles bij te leren van al die verschillende mensen die expert zijn binnen hun eigen vakgebied.

Met grootse projecten zoals de ELT is het ook belangrijk om veel geduld te hebben. We begonnen te werken aan de instrumenten in 2015. Maar daarvoor moesten we allerlei studies doen over welk wetenschappelijk onderzoek we wilden verrichten met de telescoop en over hoe we de juiste instrumenten dienden te ontwerpen om ze optimaal te kunnen laten functioneren. Dus sommigen onder ons zijn al decennia bezig met de ELT. Het gaat dan om de initiële plannen gerealiseerd te krijgen, om fondsen bijeen te brengen, om alles heel precies en gedetailleerd uit te werken en vorm te doen krijgen. En om dat alles gedaan te krijgen moet je heel veel geduld aan de dag leggen. Bovendien zal het ook nog een tijdje duren vooraleer het hele project up and running is.

Dat is dan vergelijkbaar met de bijna eindeloze tijdlijn van de James Webb Space Telescope?

Inderdaad, dit zijn zo’n grote projecten dat het werkelijk tientallen jaren duurt om significante vooruitgang te boeken. We zijn nu eenmaal bezig met erg complexe dingen, nietwaar…

Copyright afbeelding: ESO - ELT versus de piramiden van Gizeh

In België zijn we heel enthousiast over het werk van Michaël Gillon met zijn twee projecten TRAPPIST en SPECULOOS. Hij gebruikt 50 cm telescopen om aardachtige exoplaneten te ontdekken.

Dat is het mooie van het hedendaagse sterrenkundig onderzoek. Wij zijn hier bezig met dit reusachtige bouwwerk, maar niet elke interessante ontdekking wordt door een grote telescoop gedaan. Soms, zoals voor het onderzoek naar exoplaneten, heb je kleinere telescopen nodig maar met volgehouden waarnemingen elke nacht opnieuw om gegevens te verkrijgen in een tijdreeks. En daarom is het een goede zaak dat we over al die instrumenten beschikken en ze volgens hun kwaliteiten kunnen gebruiken voor al die belangrijke ondernemingen in de sterrenkunde.

Hoe kunnen we het grote publiek overtuigen dat al het geld voor die megaprojecten zoals de ELT en de JWST goed besteed geld is, zelfs in deze tijden van crisis?

Dat is altijd een moeilijke kwestie, en uiteraard zijn wij erg erkentelijk ten opzichte van de maatschappij dat wij kunnen blijven beroep doen op die financiële steun zodat wij deze projecten kunnen realiseren.

Het is te hopen dat mensen wetenschappelijk nieuwsgierig blijven. Je spreekt net over de zoektocht naar exoplaneten. Ik meen dat het grote publiek toch wel enthousiast te maken is voor het idee dat er ook planeten bestaan buiten ons eigen zonnestelsel.

Met onze grote telescopen hopen we de ontdekkingen die al gebeurd zijn verder te zetten om bijvoorbeeld de atmosferen bij sommige van die planeten te kunnen analyseren: zijn die vergelijkbaar met wat we kennen bij planeetatmosferen in ons zonnestelsel? En dan kunnen we ons afvragen of die exoplaneten mogelijk ook leven zouden kunnen herbergen. Dat zijn toch fundamentele vragen, niet? Door ons onderzoek te doen kunnen we mensen doen nadenken over deze kwesties en kunnen we hen helpen om dingen in dit verband beter te begrijpen.

Je kan ook denken aan de meer alledaagse en praktische kant van de zaak. Een groots project als de ELT biedt enorme opportuniteiten voor de Europese industrie, het is een enorme uitdaging voor wetenschappers en ingenieurs en het draagt bij aan betere mechanische en optische tools voor astronomische toepassingen, maar die uiteindelijk ook toepasbaar zijn voor andere domeinen.

De vraag of er buitenaards leven zou bestaan spreekt het grote publiek veel meer aan dan de zoektocht naar de ware aard van donkere materie en donkere energie. Zijn dat soort kwesties niet veel te abstract en te moeilijk om te begrijpen voor iemand die er niet mee vertrouwd is?

Het klopt dat het helemaal niet eenvoudig is de implicaties van dit soort kwesties werkelijk te begrijpen. Maar het heeft uiteindelijk wel te maken met de origine van het heelal en met de Big Bang. En dat is iets waar mensen toch wel van gehoord hebben en waar ze wellicht ook belangstelling voor hebben. En dan is het onze taak om dit alles voor te stellen als een boeiend astronomisch detectiveverhaal waarbij we steeds meer te weten komen over onze plaats in het grote universum.

Ik heb onlangs zitten lezen over ‘The Great Debate’, het is nauwelijks honderd jaar geleden dat we nog niet eens zeker wisten dat er sterrenstelsels waren buiten onze eigen Melkweg. Als je dan eens kijkt naar al wat we sindsdien hebben bijgeleerd over sterren, sterrenstelsels en over het heelal, dat is echt wel fantastisch…

Dankzij de wetenschap van de voorbije halve eeuw zijn we gekomen tot een steeds beter begrip van de natuurkunde met het standaardmodel der deeltjes en met de natuurkundige constanten. Maar misschien zal dit alles uiteindelijk niet zo universeel blijken te zijn als we wel graag zouden willen?

En dat is nu juist heel opwindend! Het geeft natuurlijk voldoening wanneer je een sluitende theorie hebt en je ook kan bewijzen dat die correct is. Maar het is veel opwindender als je ontdekt dat er omstandigheden en plaatsen zijn waar de fysica precies toch anders is dan wat je zou verwachten. Dan heb je meteen veel werk voor de boeg en moet je beginnen denken en speculeren over wat er precies aan de hand is. En daarom hoop ik dat we op basis van een aantal ontdekkingen in de toekomst met de ELT in vraag kunnen stellen hoe we vandaag denken over natuurkunde.

Denk je daarom dat we binnen tien, twintig, vijftig jaar onze actuele natuurkundeboeken grondig zullen moeten herschrijven door wat de ELT zal ontdekken?

Ik meen dat het erg waarschijnlijk is dat we heel verrassende dingen zullen vinden met zo’n grote telescoop. En dat we onze theorieën opnieuw zullen moeten bekijken. Of het dan echt om fundamentele natuurkunde zal gaan is een andere kwestie, maar we zullen sowieso nieuwe dingen ontdekken, dat lijkt mij zeker te zijn.

Neem opnieuw het voorbeeld van de exoplaneten. De eerste exoplaneet rond een ster zoals de Zon, 51 Pegasi b, werd veel sneller ontdekt dan astronomen hadden verwacht, want het ging om een planeet ter grootte van Jupiter maar veel dichter bij de ster dan dat Jupiter rond de Zon draait. Dat betekent iets totaal onverwachts op het gebied van hoe wij momenteel begrijpen hoe planeetvorming ontstaat bij jonge sterren, met rotsachtige planeten in het binnenste deel van het stelsel en gasreuzen in het buitenste deel ervan. Conclusie? We moeten onze ideeën over de vorming van planeten bij sterren bijstellen en opnieuw bedenken wat er zich rondom pas gevormde sterren allemaal afspeelt.

En daarom hoop je dus elke keer verrast te worden als je met een nieuw project van start gaat.

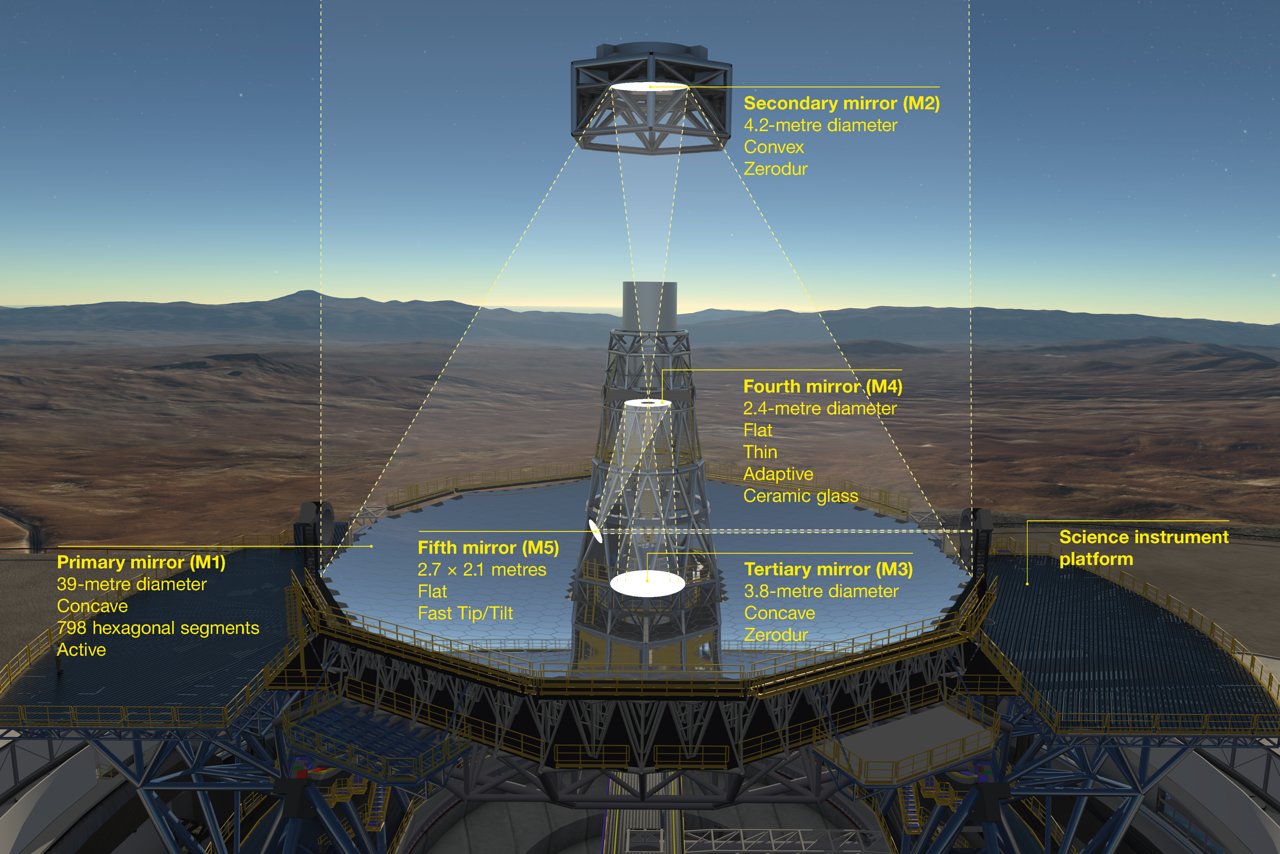

De ELT is een telescoop die bestaat uit niet minder dan vijf spiegels. Waarom werd voor zo’n constructie gekozen?

Het optische design is ongewoon, dat klopt.

Om te beginnen is er het gegeven dat de hoofdspiegel M1 met een diameter van 39,3 meter niet één enkele spiegel is. We bouwen die primaire spiegel op basis van een techniek die eerder werd gebruikt bij de Keck-telescoop op Hawaï en bij de Gran Telescopio Canarias op La Palma die een kopie is van de Keck. We hebben geopteerd om de reusachtige spiegel op te bouwen door een grote hoeveelheid zeshoekige segmenten heel precies naast elkaar te zetten tot we een cirkelvormige structuur krijgen van bijna veertig meter diameter. We kunnen de positie van elk segment afzonderlijk heel nauwkeurig controleren zodat we op het eind effectief één gigantisch spiegeloppervlak bekomen. In die hoofdspiegel zullen maar liefst 798 hexagonale segmenten zitten. De serieproductie van al die componenten om onze M1 te maken is een erg interessant en uitdagend onderdeel van het hele project.

Naast die hoofdspiegel zijn er vier andere spiegels nodig om het optische systeem van de ELT te vervolledigen, zoals je kan zien op de schematische weergave.

Copyright afbeelding: ESO ELT lightpath

Het licht wordt gereflecteerd van bij de hoofdspiegel van de telescoop via de convexe spiegel M2 met een diameter van 4,2 meter naar de concave derde spiegel M3 die een diameter heeft van 3,8 meter.

Vervolgens hebben we een vlakke spiegel, M4, die heeft een diameter van 2,4 meter en is voorzien van adaptieve optiek. Dat betekent dat deze spiegel wel duizend keer per seconde van vorm kan veranderen zodat er op die manier kan gecompenseerd worden voor turbulenties in de atmosfeer. Die zijn er immers verantwoordelijk voor dat het sterlicht wanneer het door de lucht passeert door die turbulenties negatief beïnvloed wordt, en zo raakt het sterlicht enigszins vertroebeld. En dankzij de adaptieve optiek kunnen we deze twinkelingen of atmosferische effecten corrigeren door ze te meten en meteen te neutraliseren.

En ten slotte is er M5, de vijfde spiegel in de optische keten. Dat is een vlakke schuinstaande spiegel van 2,7 bij 2,2 meter. Ook deze spiegel draagt bij aan de adaptieve optiek van de telescoop, en hij leidt de lichtbundel naar het platform naast de telescoop waar alle wetenschappelijke instrumenten van de ELT opgesteld staan.

ESO doet ook inspanningen om de CO2-voetafdruk van de ELT danig te beperken?

Dat klopt. Door de installatie van een vermogensoptimalisatiesysteem en een fotovoltaïsche opstelling op de site van de ELT zet de ESO een belangrijke stap in de zogenaamde vergroening van het hele project.

De woestijn in Chili is een gebied met gedurende het hele jaar heel veel zonneschijn. De energie die we zo uitsparen zal significant zijn, aangezien de ELT de meeste energie overdag zal verbruiken om de temperatuur van de telescoop en van alle optiek in de koepel op een constant peil te houden.

Onze programmamanager Roberto Tamai was in juni dit jaar (2022) op de Cerro Armazones in Chili waar de ELT gebouwd wordt om deze installatie op basis van zonne-energie plechtig in te huldigen. Onze fotovoltaïsche installatie zal ook als back-up dienen voor de regio Antofagasta, aangezien ze het mogelijk maakt om via het net energie te leveren aan de lokale gemeenschap in geval van een wijdverspreide stroompanne.

Hoe ver zit het eigenlijk met de bouwwerkzaamheden?

De locatie waar de ELT gebouwd wordt is bovenop een berg met als naam Cerro Armazones in de Atacama, een woestijn in het noorden van Chili. Die plek is ook niet ver van de berg Paranal waar de VLT opgesteld staat, ongeveer 45 minuten rijden.

We zijn al enkele jaren bezig met de bouw. Eerst moesten we de top van de berg afplatten om een groot platform te maken. Daarna werden de funderingen met veel staal en beton geïnstalleerd. En in die funderingen dienden we meerdere seismische isolatoren te integreren, dat zijn mechanische ingrepen die bij aardbevingen compenseren voor het schokken van de bodem. Dat is nodig want er zijn vaak aardbevingen in Chili.

Als je kijkt naar de laatst beschikbare beelden van de webcams op Cerro Armazones, dan zie je dat ze momenteel bezig zijn met de muren van het gebouw waarop de koepel zal geconstrueerd worden. En veel van het staal dat we gaan gebruiken voor de bouw van de reusachtige koepel is al aanwezig en wordt in werkhuizen geassembleerd.

Het is echt heel opwindend om te zien hoe ons project geleidelijk aan begint vorm te krijgen. En eens we de kromming van de koepel zullen zien verschijnen, dat zal echt fantastisch zijn. Dus men is daar in de Chileense woestijn druk bezig, en dat gaat nog wel enkele jaartjes blijven duren.

Copyright afbeelding: ESO ELT webcams

Wanneer mogen we ‘first light’ verwachten?

Dat zou in 2027 moeten zijn. En dat is ook het moment waarop we alle instrumenten bij de telescoop installeren. Dus dat is nog wel enkele jaren werken met alle betrokkenen tot alles klaar is.

Het zou met de lichtkracht van de ELT mogelijk moeten zijn om het wiebelen van sterren waar te nemen ten gevolge van aardachtige planeten die eromheen draaien?

Dat is één van de vele targets die we met onze ELT willen proberen te realiseren. Met die techniek om het wiebelen van sterren te meten zijn astronomen intussen zeer goed vertrouwd, en er zijn op basis daarvan al heel wat exoplaneten ontdekt. Met de ELT kunnen we de grenzen serieus verleggen naar steeds kleinere sterbewegingen, en dat is zeker een belangrijk doel dat we met deze methode willen bereiken: het opsporen van planeten die helemaal gelijken op de Aarde.

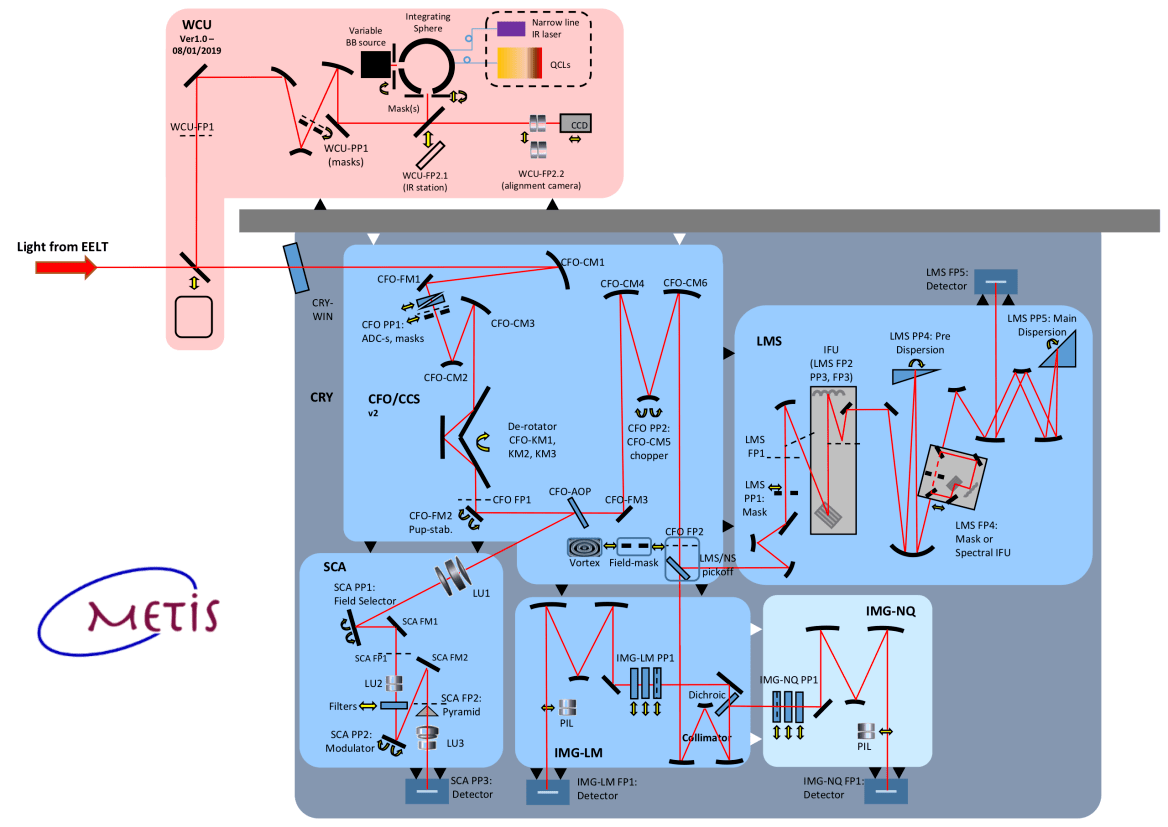

De universiteit van Leuven is betrokken bij het METIS-instrument op de ELT?

Inderdaad, het Instituut voor Sterrenkunde in Leuven maakt deel uit van een internationaal consortium van twaalf instituten, en Leuven heeft een mooi aandeel in METIS. Men deed er heel wat werk in verband met de verschillende aspecten van het waarnemen van exoplaneten, maar ook voor de controlesoftware van het instrument. METIS staat voor Mid-IR ELT Imager and Spectrograph, en is zoals de naam het zegt een krachtige spectrograaf en beeldsensor met een hoog contrast.

Copyright: Leiden Observatory

METIS, één van de zes voorgestelde wetenschappelijke instrumenten bij de ELT, zal het astronomen mogelijk maken de fysische en chemische basiseigenschappen van exoplaneten te onderzoeken, zoals hun baangegevens, temperatuur, helderheid en samenstelling en dynamiek van hun eventuele atmosferen.

METIS zal ook objecten in het zonnestelsel bestuderen, stofschijven rond sterren en stervormingsgebieden, bruine dwergen en het centrale deel van de Melkweg, sterren in alle evolutiefazen en de actieve kernen van sterrenstelsels.

Wat zijn andere wetenschappelijke doelen van de ELT?

Onze telescoop zal het mogelijk maken om terug te kijken naar de verst verwijderde objecten in het universum, en dat kan ons leiden tot een beter begrip van de vorming en de verdere evolutie van de eerste sterren, sterrenstelsels en zwarte gaten in het heelal, plus hun onderlinge relaties.

Met de ELT zouden we ook moeten in staat zijn om de versnelling te meten van het uitdijend universum. Die bevindingen zullen ons het heelal in zijn geheel beter doen begrijpen.

En misschien ontdekken we eveneens variaties bij de fundamentele natuurkundige constanten. Indien dat het geval is, zou dat verstrekkende gevolgen hebben voor ons begrip van de wetten van de fysica.

Er zal natuurlijk samengewerkt worden met tal van andere sterrenkundige onderzoeksprojecten?

We kijken er in ieder geval hard naar uit om voor een opvolging te zorgen voor al die spectaculaire ontdekkingen van de JWST. Van in het begin gingen we ervan uit dat de ELT en de JWST complementaire instrumenten zouden zijn. De ELT zal de observaties van de JWST meer gedetailleerd kunnen opvolgen in die zin dat we kleinere details kunnen onderscheiden en een hogere spectrale resolutie kunnen halen.

En natuurlijk heb je ook ALMA, dat ander groot observatorium van de ESO in het noorden van Chili. ALMA is de Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. Het is een interferometer die bestaat uit 66 zeer nauwkeurige schotelantennes die verspreid staan over afstanden tot 16 kilometer. De ELT en ALMA zullen zonder twijfel ook heel compatibel zijn.

Soms vragen bezoekers op Volkssterrenwacht MIRA of we hen met onze telescopen de Amerikaanse vlaggen op de Maan kunnen tonen. Natuurlijk zijn onze telescopen daar veel en veel te klein voor. Maar zelfs met een 40 meter telescoop zou dit niet mogelijk zijn, nietwaar?

Inderdaad. Ooit droomden we ervan een 100 meter telescoop te bouwen, ik herinner me toen berekend te hebben dat zelfs zo’n monstertelescoop daarvoor niet groot genoeg was.

Wat denk jij persoonlijk over het bestaan van buitenaards leven, Suzanne?

Ik ben er vrij zeker van dat het moet bestaan. Het heelal is zo ongelooflijk groot dat ik niet geloof dat wij alleen zijn. Of we ooit in staat zullen zijn om dat buitenaards leven te detecteren of om het te ontmoeten? Daarover heb ik wel sterke twijfels dat dit zou gebeuren nog tijdens mijn leven. Maar ik geloof echt wel dat er ergens anders nog iemand anders moet zijn…

En heb je een favoriet astronomisch beeld?

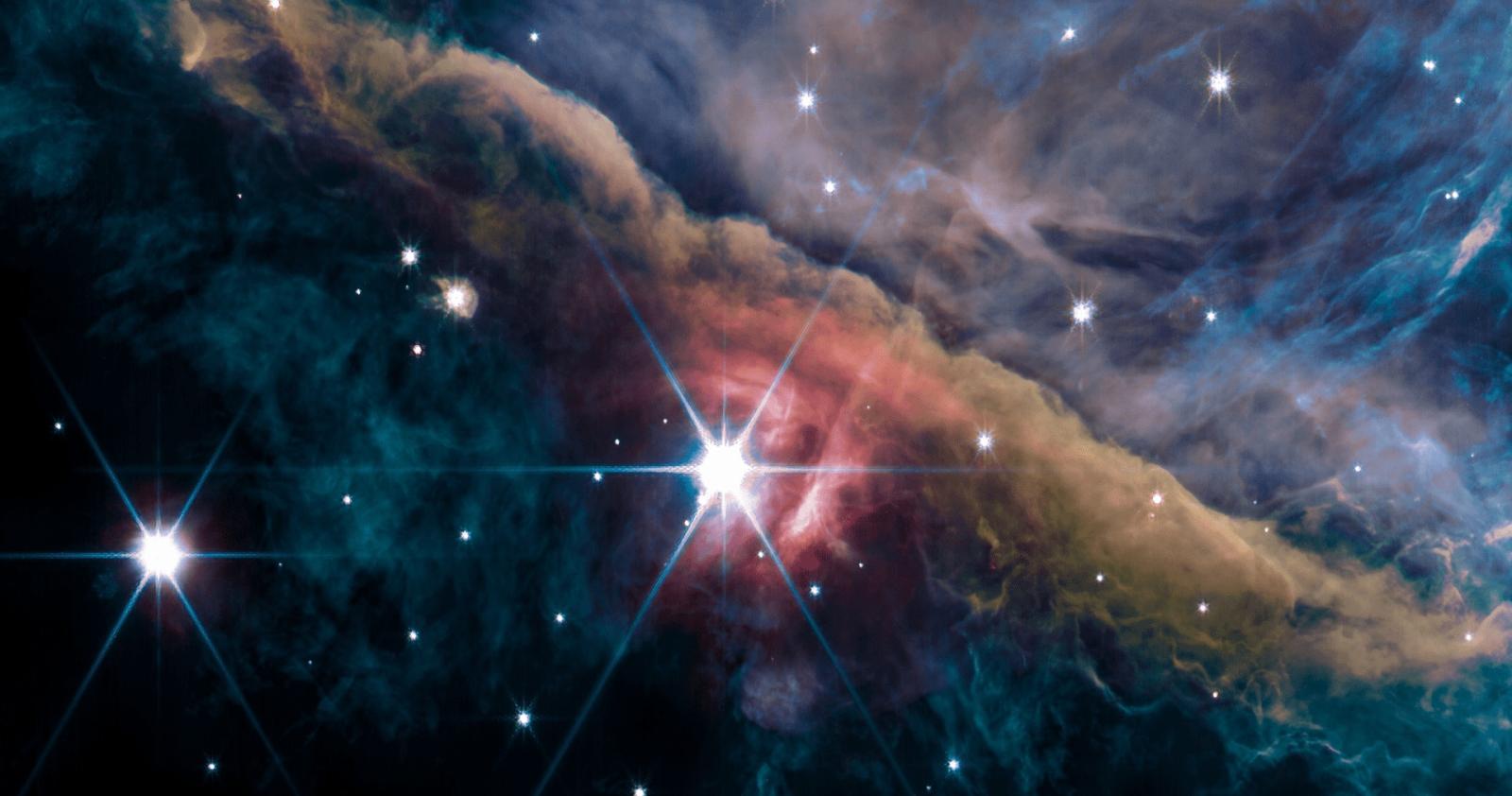

Ik ben echt wel een fan van de Orionnevel. Elke keer als er een nieuwe telescoop met zijn waarnemingen begint, kijk ik benieuwd uit naar intrigerende beelden die er gemaakt worden van dit gebied ten zuiden van de Gordel van Orion.

Zoals ik eerder zei ben ik sterk geïnteresseerd in stervorming, en daar, op een afstand van zowat 1.340 lichtjaar, bevindt zich het meest nabije gebied waar op hoog tempo sterren gevormd worden. De Orionnevel kan je zien als een schatkist, elke keer als je kijkt met een nieuw instrument ontdek je nieuwe juweeltjes. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan dat prachtig beeld dat de JWST onlangs vrijgaf.

Copyright afbeelding: NASA, ESA, CSA, PDRs4All ERS Team & Western University Ontario

Eén van mijn favorieten is het Hubble Ultra Deep Field.

Akkoord, de Hubble Deep Fields zijn onwaarschijnlijk boeiende foto’s. Gewoon al de verrassing als je naar een stukje hemel kijkt dat helemaal leeg lijkt te zijn en dat er daar dankzij die opname duizenden sterrenstelsels te zien zijn in het jonge heelal. Sinds die opnames gemaakt werden is er heel veel follow-up geweest, omdat het gaat over materiaal dat zo belangrijk is voor het begrijpen van het ontstaan en de evolutie van sterren en sterrenstelsels. En dat is dus ook één van de targets die wij zullen gebruiken om te zien waartoe onze ELT in staat is.

Hartelijke dank voor dit interessante gesprek, Suzanne. Ook wij kijken vol ongeduld uit naar 2027 en het nieuwe tijdperk in de sterrenkunde dat zal aanbreken wanneer de ELT operationeel zal worden.

Tekst: Francis Meeus, september 2022

***********************************************************************************

Interview in English

Hello Suzanne, it is nice to get in touch with you thanks to Skype. How did you get involved in astronomy?

Comparatively late I think. It was when I was at university that I really decided astronomy was the path that I wanted to follow. I started to do a degree in physics at the university of Glasgow which is where I am from. You do physics, you do maths, you have to find another subject and I chose to do astronomy. It was from then that I got really quite engaged with the topic and that I realised what a fascinating way it is to explore the world of physics: the universe is indeed a very interesting and unique laboratory. And when I did my PhD I got really interested in the more practical side: building the instrumentation for astronomy.

As a youngster, you never went to a star party to be overwhelmed by the beauty of Saturn’s rings or by similar things?

I really wasn’t one of those kids. I did get some lessons about the constellations from my father and I remember seeing a lunar eclipse when I was young. But it wasn’t really one of my passions as a kid. It came more gradually.

How did your path in astronomy evolve from the university of Glasgow to ESO, the European Southern Observatory? What happened in between?

I went directly from finishing my undergraduate degree to doing my PhD. And I didn’t travel very far actually, I landed at the university of Edinburgh for my PhD. It is located at the Royal Observatory at Blackford Hill in Edinburgh.

And there I already started working on an instrument project which was already quite a lot advanced. Parts of the instrument were already in the lab and it was close to being delivered to the telescope at that point. I got involved in working for this project and also doing some astronomical research in the area of star formation. The project was an infrared spectrograph that was being built for the United Kingdom Infra-Red Telescope, the UKIRT, which is on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. So for my PhD I had the fantastic experience of being able to go to the telescopes in Hawaii and install the instrument.

After that, I was pretty lucky because I could stay in Edinburgh for a long time. I had a staff position at the Observatory and stayed there almost twenty years. At that time I was working on an instrument project for ESO that was to be delivered to the Very Large Telescope in Chile. And I was already very interested in developing the instruments for the Extremely Large Telescope that ESO was planning since the late 1990’s.

So when the position came up to move to the instrumentation division at ESO, it was a very exciting opportunity. I was really lucky to get it and very happy to be allocated to work at the ELT instruments project.

How does it feel to be part of the ELT, probably the biggest optical telescope ever?

It is certainly the biggest optical ground-based telescope that is being built now, that is for sure. But whether anybody comes later and decides to build a bigger one, we shall see.

And yes, also the instruments are huge and really challenging, so it is very exciting. Everything we are doing is new. It is sometimes quite scary when you think about how big these instruments are, what it takes to build them, the hundreds of people working on it. So we are really working hard to get it right and so we can do all those exciting scientific discoveries that we are looking forward to. It is a gigantic project with teams building instruments distributed around Europe, we do literally have hundreds of scientists and engineers working. So it is fun being part of that, and knowing and learning from all of those people with their different expertise.

But with huge projects like the ELT, you also have to be very patient. We started working on these instruments in 2015. But before that, we had a long period of doing design studies, and exploring the scientific projects that will be done with the telescope. So it has been decades for some of us to put the planning into place, to raise the money, to work out exactly what to do and to do all the design work. Therefore, you have to be quite patient. And we still have some time to go as well before the project is up and running.

Comparable with the almost endless timeline of the James Webb Space Telescope?

Indeed, these projects are so big they really take decades to move forward. We are doing pretty complicated things, you know…

In Belgium we are very enthusiastic about the discoveries of Michaël Gillon with his TRAPPIST and SPECULOOS projects. He is using 50 cm telescopes to discover exoplanets.

That is the nice thing about astronomy today. We are working on this colossal project, but not every discovery comes from a huge telescope. Sometimes, like for the exoplanets studies, you need a small telescope but with observations every night to get time series information. So it is good that we can take all of these tools and use them for all these important topics.

How can we convince the general public that the funds for all these huge projects like the JWST and the ELT is money well spent, even in times of crisis?

It is always a difficult question, and we are certainly very grateful that we continue to have the support so that we can turn these projects into reality. Hopefully people remain scientifically curious. You mention about exoplanet research. I think people can really be excited about the idea that there are planets outside our solar system. With our big telescope we hope to continue the work that is already happening about understanding what is in the atmospheres of these planets: are they comparable to what we find in our own solar system? And this leads us to thinking about whether they sustain life. Topics like this which are very fundamental, right? So in doing our job, we can inspire people to think about these questions and we can help to understand.

You can also think about the more everyday aspects. A big project like the ELT offers an opportunity to European industry, it is challenging for scientists and engineers and it contributes to better mechanical and optical design for astronomical applications, but then it is also usable in other fields.

The question of extra-terrestrial life is more exciting for people in general than the nature of dark matter and dark energy. Aren’t those questions too abstract and too hard to understand for someone who is not familiar with these subjects?

It is indeed hard to really understand the implications of these topics. But it is about the origins of the entire universe and related to the idea of the big bang. And that is something people do have in their minds. It is up to us to present all this as an interesting astronomical detective story where we learn more and more about our place in the universe.

I have been reading about the Great Debate, it is only a hundred years ago that we didn’t really know that there was a galaxy outside our Milky Way. If you see everything that we have learned about then since then and how cosmology evolved since, that is really a fantastic story.

We are relying on an always better theory of nature with the standard model and with physical constants. But these findings are maybe not as universal as we like to think?

And that is very exciting! It is certainly satisfying when you have a theory and you can prove that your theory is correct. But of course it is more exciting if you discover that there are places where physics is a bit different. Then there is much more to think about and to speculate about. So I hope that some of the future discoveries with the ELT could challenge how we think of physics today.

And do you expect that with the discoveries of the ELT we will have to rewrite our actual books of physics in ten, twenty, fifty years?

I think it is entirely likely that we will find things that are completely surprising with such a big telescope. And that we will have to look again at our theories. Whether that will be absolute fundamental physics, that is another question, but there certainly will be something.

Take again the example of exoplanets. The first exoplanet discovered around a sun like star, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered much faster than astronomers expected because it is a planet the size of Jupiter but much closer to its parent star than Jupiter is to our Sun. That means something completely unexpected in terms of our understanding of planet formation with rocky planets in the inner part of the planetary system and gas giants in the outer part of it. Conclusion? You have to reinvent planet formation and think again about how this should happen. So anytime you try something new, you definitely hope to be surprised.

The ELT is a telescope with no less than five mirrors. Why this type of construction?

The optical design is unusual, indeed.

The first thing to comment about is that the primary mirror of the telescope with a diameter of 39,3 meters isn’t just one mirror. We are building on a technique that has been used at the Keck Telescope in Hawaii and on the Gran Telescopio Canarias which is a copy of the Keck. The construction is one huge mirror, composed of many hexagonal segments. You control the position of every segment very precisely so that you end up with effectively one gigantic mirror surface. We are going to have 798 hexagonal segments in our primary mirror, the M1. The serial manufacture of all of the components that it takes to make our M1 is really an interesting and challenging part of the whole project.

And then in addition to the first mirror we have four other mirrors to complete the optical system of the ELT, as you can see in the illustration (see below).

The light is reflected from the telescope's primary mirror via the convex M2 mirror with a 4,2 m diameter to the concave tertiary mirror M3 with a 3,8 m diameter.

Then we have the 2,4 m flat mirror M4, equipped with adaptive optics. This mirror is capable of changing shape as much as a thousand times in one second so that we can compensate for the turbulence in the atmosphere which influences the starlight as it passes through the atmosphere and blurs it slightly. So we can correct these twinkling or atmospheric effects by measuring them and by correcting very quickly with this excellent technique.

Finally there is M5, the fifth mirror in the optical chain, a flat 2,7 by 2,2 m tilted mirror. This mirror also contributes to the telescope's adaptive optics and is guiding the light beam to the platform beside the telescope with all the ELT science instruments.

ESO is also doing efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of the ELT?

That’s right. With the installation of a power conditioning system and a photovoltaic plant at the site of the ELT, ESO takes an important step to make the whole project greener.

The Chilean desert is an area that receives during the whole year a high amount of solar radiation. The saved energy will be significant, since the ELT will consume most energy at daytime to stabilise the temperature of the telescope and its optics inside the dome.

Our programme manager Roberto Tamai went to Chile in June of this year (2022) to do the inauguration of this solar power based project. The photovoltaic plant will also serve as a backup energy plant to the region of Antofagasta as it will be able to supply energy to the local community via the grid in case of a widespread power outage.

What is the status of the construction?

The location of the ELT is on top of a hill called the Cerro Armazones in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile, it is not far from the VLT on Paranal, about a 45 minutes’ drive.

We are already building on site, with the construction work already going on for several years. First of all we had to level the top of the mountain to create a big platform, then followed the building of the foundations with a lot of concrete and steel. But we had to integrate in these foundations several seismic isolators, mechanical features that can compensate for earthquakes. A good thing, because we have a lot of earthquakes in Chile.

If you look at the latest available images of the webcams at Cerro Armazones, you can see that they are actually building the walls of the building on which the dome will be constructed. And a lot of the steel we are going to use for the construction of the giant dome is already on site assembled in warehouses.

It is really very exciting to see the project rise above the ground. And when we will start to see the curve of the dome, that is going to be quite something. So there is a lot of work going on there down in the desert in Chile. And this will continue for a number of years.

When do you expect first light?

The moment we are expecting first light will be in 2027. And that is also the moment when we will start to put the instruments onto the telescope. So there is still a few years ahead of working with everybody until we get that done.

With the light gathering power of the ELT, it would be possible to see the wobbling of earth like planets?

That is very much one of the targets for the telescope to try. That technique of measuring the wobble of stars is of course very well established and many planets having been discovered that way. With the ELT we can push the limits to smaller and smaller motions, and that is definitely one of the things we want to detect with this method: near earth twin planets.

The university of Leuven is involved with the METIS-instrument?

Exactly, the Institute of Astronomy at the Leuven university is part of an international consortium of about twelve institutes and they have got quite a nice part in METIS. They did a lot of work on the aspects related to exoplanet observations but also on the control software of the instrument.

METIS stands for Mid-IR ELT Imager and Spectrograph and is a powerful spectrograph and high-contrast imager.

METIS is one of six proposed instruments for the ELT and will allow astronomers to investigate the basic physical and chemical properties of exoplanets, like their orbital parameters, their temperature, luminosity and the composition and dynamics in their atmospheres. METIS will also contribute to the study of Solar System objects, circumstellar discs and star forming regions, properties of brown dwarfs, the centre of the Milky Way, the environment of evolved stars, and active galactic nuclei.

What are other scientific goals of the ELT?

Our telescope will allow us to look back to the most distant objects and that can help understand the formation and subsequent evolution of the first stars, galaxies and black holes plus their relationships.

With the ELT, we should be able to measure the acceleration of the universe's expansion. Those results will enlarge our understanding of the universe.

And maybe we discover variations in the fundamental physical constants. If so, that would have far-reaching consequences for our understanding of the laws of physics.

There will be a lot of collaborations with other astronomical projects I suppose?

We are very much expecting to follow up all of these exciting JWST discoveries. We always had in mind that the ELT and the JWST would be complementary facilities. We can follow up with more detail the JWST observations in terms of smaller features and higher spectral resolving power.

And of course there is ALMA, the other big facility of ESO in northern Chile. Without any doubt, the ELT and ALMA will be very compatible.

Now and then visitors at the MIRA Public Observatory ask us if we can show them with our telescopes the American flags on the Moon. Our telescopes are much too small to do so. But even with a 40 m telescope this wouldn’t be possible?

Not quite. Once upon a time when we were dreaming of building a 100 m telescope, I recall me to have worked out that even such a behemoth is not big enough to do so.

What do you personally think about extra-terrestrial life, Suzanne?

I am pretty sure it must exist. It is a very big universe and I don’t believe we are alone. Whether we will ever be able to detect or meet or prove that there is another species out there? I have my strong doubts that this will happen in my lifetime. But I do believe there must be somebody else somewhere.

And do you have a favourite astronomical picture?

Actually I am a fan of the Orion nebula. Any time there is a new facility, I like to see the fascinating images of that region south of Orion’s Belt. As you know, I am interested in star formation and there, at a distance of about 1.340 lightyears, is situated our nearest example of high mass star formation. The Orion Nebula is such a box of treasures, every time you look at it with a new facility, you discover new things. Think of the beautiful photos the JWST released recently.

One of my favourites is the Hubble Ultra Deep Field.

I agree, the Hubble Deep Field is incredible. Just the surprise when you look at a zone that is supposed to be empty and to discover there thousands of galaxies in the young universe.

Since the Hubble Deep Fields were taken, there has been so much follow up because they are so important for our understanding of the origin and the evolution of stars and galaxies.

And it is also one of the targets that we will use to explore the performance of our telescope.

Well, Suzanne, thank you very much for the interview. We are looking forward impatiently to 2027 and the new era of astronomy that will begin with the ELT.